Illustration by Clifford Harper/agraphia.co.uk

Collected Poems by Hope Mirrlees

Patrick McGuinness

Fri 13 Apr 2012 22.50 BST

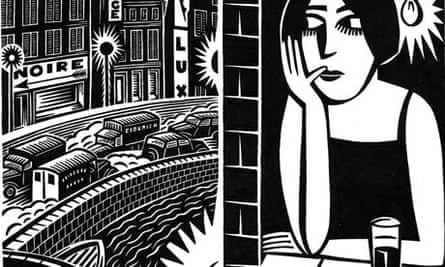

What this "mystical experience" might feel like, and what the "aural kaleidoscope" might look and sound like, can be seen in her long poem "Paris", written in 1919 and published by Virginia Woolf's Hogarth Press in 1920. Woolf called it "indecent, obscure, brilliant", and the poem describes (the word "describes" is inadequate: it dynamically enacts, verbally and with an array of compelling visual and typographical effects) a day in post-first world war Paris.

"Paris" is the product of immersion: not just in Parisian high culture, but in a seamier, more disjointed and immediate kind of metropolitanism. Voices, machine noises and musical notes are caught in mid-air, shreds of advertising, brand names, logos, street signs and even the lettering on monuments, are conveyed in poetry that takes liberties not just with standard verse forms, but with linear writing itself.

It's the Paris of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Apollinaire, of cubism and surrealism, jazz culture and nightlife. It is a place of many pasts, with its ruins and its dead (there are several allusions to the war, and to the 1919 Paris peace conference), but also of multiple presents. Mirrlees writes from the point of view of the "flâneuse": dreamlike, but retaining the broken edges of urban experience, the almost filmic shifts between slow-motion and speedy blur.

The poem could be disorientating, but it holds together because Mirrlees lets us enter the dream, reassuring us from the start that any disorientation is part of the experience and not a barrier to it. "I wade knee-deep in dreams … the dreams have reached my waist", she writes, and there is a sense of a poetic voice being both crowded out and submerged. At the same time, she notes everything with precision: she sees, reads, hears, smells, tastes and touches, and there's an exhilarating mix of sophistication and rawness in the writing. One minute we're in the Louvre, the next we're catching wafts from the Paris sewers:

There is also a real engagement with lived reality: war, displacement, poverty, venereal disease, rural depopulation (Paris may be the world's artistic capital but it is also "a huge homesick peasant"), and urban hardship. The poem plays on metaphors of surface and depth: the Métro, the sewers, the shady demi-monde on the one hand, the art works, monuments, galleries on the other. The most ferocious instance of this metaphor comes in the line "Freud has dredged the river and, grinning horribly, / waves his garbage in a glare of electricity", where the unconscious is posited as modernity's own underworld, our own cloacae.

Despite this, the dominant feeling in the poem is of happy excess. There is no sense in Mirrlees, which we find in her friend Eliot, that modern life cheapens and dulls us. On the contrary, there is always more in one minute of modern life – "Little funny things ceaselessly happening" – than there is space for in any book, symphony or canvas. "Paris" predates The Waste Land by two years, and though it is less achieved and resonant than Eliot's poem, it is, in an English context, just as experimental and unprecedented. It is also full of wit, freshness and clever bilingual punning – "silence of the grève" for a workers' strike, "an English padre tilt[ing] with the Moulin Rouge", it is a sort of cousin to The Waste Land, and perhaps even its optimistic antidote.

Mirrlees was born in Kent in 1887, and died in 1978. After "Paris", she published no poetry for nearly 50 years, and her poems of the 60s bear no sign of her earlier radicalism, though many are impressively stringent in their thinking.

This edition includes several essays, an introduction by Sandeep Parmar, and a definitive commentary on "Paris" by Julia Briggs, who did more than anybody else to bring Mirrlees out of obscurity. It is a pleasure to see Briggs's careful, elegant advocacy of what she calls Mirrlees's "lost modernist masterpiece" finally bear fruit in this fine edition.

• Patrick McGuinness's Jilted City is published by Carcanet.

.jpg)

0 Yorumlar